For more information about our hunting safaris, don’t hesitate to reach out and contact us!

Bookends

by Steven Shaffer

(Lincoln, NE, USA)

Campfire

This is not a hunting story, properly. It is, however, a story about hunting. There are no detailed descriptions of thunderous impacts, flat trajectories and fine optical instruments; not that there is anything in the least wrong with those things, but to speak of these things as being hunting is similar to focusing on a jockey’s boots and calling it horse racing. Both are necessary, but there is so much more to the endeavor to experience.

When I recall a hunting trip, it comes back to me in bits and pieces, and the chronological stream is often interrupted or forgotten. Much of the logistics and tedium is glossed over, and what remains are the pillars that support the experience, the foundation; the heart of things. The Bookends.

It is June, two weeks shy of July in fact, yet the light that filters down through the rustling, dry leaves has a decidedly autumnal slant to it. The air is dry, and cool, and there is an underlying smell of dusty-dry vegetation that is familiar to any North American who has spent time in the woods on an early November day. Despite the almost crushing fatigue born of a long travel, I am anxious to hold a rifle; to shed these traveling clothes and get out of the city.

For now, though, I am content to be able to sit in the sun, with my legs stretched out in front of me in the comfortable hostel chair. I see the vehicle of my Professional Hunter, (or "The PH", as he jokingly refers to himself) pull into the parking lot, and we are off to meet the rest of the family for dinner.

I am crawling in the clean iron-red sand of the Kalahari, and taking a fair amount along with me, from the feel of it. The PH and I hug the treeline to keep the herd of Gemsbok from spooking, as they have already done multiple times today. In fact, earlier we had decided to stop stalking a particular herd and just quietly backed away to start over with another group. The animals are too wary, too gifted in eyesight and sense of smell to give you more than one or two chances. Even now, despite our best efforts, we find ourselves pinned down once again, unable to continue our progress without spooking the whole herd. So we lay, prone in the sand and hoping for something to change.

Making a fist, I rest my chin on it and think about what I have experienced already; the tiredness and pains and uncertain feelings that come along with the moments of elation and accomplishment. Everything around me reminds me that I am not at home anymore, but 20 hours of hanging in the sky, and 10,000 long miles away.

As if I need another reminder, I see a white something in the sand, just inches from my face, with big pincing mouthpieces affixed to an over-bulked head. I can’t tell if it is too cold to move, or dead, or maybe just sleeping through the Namibian winter, dreaming of warmer days and wood to chew.

I am thinking about termite mounds and tall horns when I drift off to sleep, and if I dreamt, I don’t remember.

The air is just as still as it could be, and with only the quiet hiss of the fire, you can almost talk yourself into believing that the heartbeat in your ears is real, and not just your imagination.

The moon is already up, and bright, but even before the daylight light completely fades you can see Acrux starting to show, faintly, then Mimosa, and you know that by the time the bright fire burns down to red, smokeless cooking coals, you’ll again have the Southern Cross overhead to remind you where you sit in the world.

Now that you’ve taken the edge off with a jot of Scotch, as smooth and smoky as the Camelthorn fire, you’re ready to strip off boots and socks, and work your tired toes deep into the cool red Kalahari sand…now you have some home-grown massage therapy while you enjoy your “bushman TV.” You let a small bit of self-awareness ruin the scene for just the tiniest moment, and try to focus on the now. You know there come a time in the future when you will remember, and miss these scenes almost bitterly…but that time is not now, and now is so very good that it is enough.

In slowness of African time, you realize that the fire is low and your glass is empty, and probably has been for some time. If you stir now from your warm, drowsy perch, you have time for one more drink before the air turns to nirvana with the smells of your meal, so under the peaceful light of Crux, with sore legs and a catch in your back, you stiffly wobble off to find the bottle.

It feels like an extravagance to have a dirty rifle, with still more hunting to come in the upcoming days. Even though I know that the piece is plenty clean to work just fine for a few more days, it is cleaned and wiped down if only to placate myself. Shooting is really just a mind-game waged against our own muscles, bones and joints, and I’ll take any advantage, real or imagined, that I can muster. Just like a clean automobile’s motor seems to purr like a contented kitten, a rifle that has had a few pats from an oily rag and fingerprints rubbed off the stock, and perhaps a dry-patch or two through the bore, will group better by half over one that has not.

For the most part, we hunters are creatures of habit; this was the way we were raised. Heaven forbid we try to fall sleep with a wet rifle standing in the corner, and sand in the action grates not just on the steel of the rifle, but also on our soul. It is a mind-soothing thing as well to know everything is taken care of, and to those that say a rifle is just a tool, the meager sum of its parts, or a lowly machine? Bosh. Mine at least are well-loved combinations of wood, steel, glass leather and rubber that I can feel in my empty hands upon closing my eyes to sleep, the night before the hunting horns sound.

Though I am too fickle to limit myself to one or two, or even three or five, each has their own personality and manner, and I know them complete from crown to toe.

High on the rocky slopes of the Khomas Hochlands, I am grateful for many things…not the least of which is the fact that I find my weary self on the back of a horse, rather than under my own power, for the trip back to the ranch. I am no real equestrian, but I find a slow sway to match the cadence of the steps of my mount that is comfortable for me, and hopefully the steady mare as well.

The sounds of shod hooves on the shale is soothing, and I find my head hanging, and I have to remind myself to stay in the saddle, fighting to keep my eyes open. Luckily the mare under me needs no direction from her rider, and I am happy enough to leave the choice of path up to her discretion.

The pace, too, is fine enough for me, but slightly slower than the others, and I look up to see the tracker turn around in his saddle, frowning at the space between us. "You must punish her", he says, pointing to the leather strap hanging to the rear of the saddle while making slapping motions with his arm. I am a guest here, and I make to do as I am told and loosen the strap from the loop and preparing as if to give the horse a snap or two on the flank. The tracker, satisfied, turns back around in his saddle.

The gentle swat I deliver could only be punishing to the mare’s ego, but the pace does quicken, and I soon find myself joining the rear of the group again. I begin to notice, however, that the previously ample berth I was afforded around the Camelthorn trees and hook-barbed acacia has now shrunk, and hat, shirt and skin are all in danger from the sharp nettles spiking the branches. Touché, and well-played.

Bending down to pat the neck of my mount, I whisper, "point taken", and declare a truce, vowing to leave the pace-making up to the sure-footed mare from then on.

Comments for Bookends

|

||

|

||

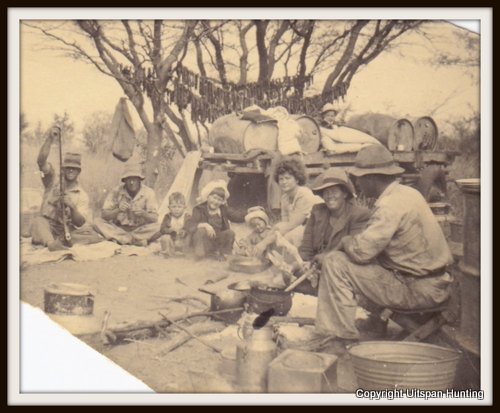

Meaning of "Uitspan"

'Uitspan' is an Afrikaans word that means place of rest.

When the Boer settlers moved inland in Southern Africa in the 1800's, they used ox carts. When they found a spot with game, water and green grass, they arranged their ox carts into a circular laager for protection against wild animals and stopped for a rest.

They referred to such an action of relaxation for man and beast, as Uitspan.

(Picture above of our ancestors.)

Did you know? Greater Southern Kudus are famous for their ability to jump high fences. A 2 m (6.56 ft) fence is easily jumped while a 3 m (9.84 ft) high fence is jumped spontaneously. These strong jumpers are known to jump up to 3.5 m (11.48 ft) under stress. |

Did you know? Some animals have one sense more than man!The flehmen response is a particular type of curling of the upper lip in ungulates, felids and many other mammals. This action facilitates the transfer of pheromones and other scents into the vomeronasal organ, also called the Jacobson's Organ. Some animals have one sense more than man!The flehmen response is a particular type of curling of the upper lip in ungulates, felids and many other mammals. This action facilitates the transfer of pheromones and other scents into the vomeronasal organ, also called the Jacobson's Organ.This behavior allows animals to detect scents (for example from urine) of other members of their species or clues to the presence of prey. Flehming allows the animals to determine several factors, including the presence or absence of estrus, the physiological state of the animal, and how long ago the animal passed by. This particular response is recognizable in males when smelling the urine of a females in heat. |