For more information about our hunting safaris, don’t hesitate to reach out and contact us!

Bookends, Part Two

by Steven Shaffer

(Lincoln, Nebraska, USA)

Kudu

I saw the Kudu in the yellow afternoon light before the PH did, and it was a matter of a long session with the field glasses before we decided that it was a good enough animal to warrant a closer look.

"If we can get close enough for a good shot, and it is a good bull, I want to take this animal" I said, already feeling that this was my bull.

I ran the bolt on the big Mauser, quietly working the long brass and copper cartridge into the chamber; an action that always felt like a statement to the effect of, "things just got serious" and I felt the first effects of adrenaline and taut nerves start to set my heart racing. I double-checked the safety catch, slung the rifle and set off after my fluidly-moving guide. We worked our way carefully, using what cover we could find and placing our steps carefully as the big animal continued to feed.

Finally we managed to close the distance that afforded a better view of the majestic antelope. I knew the PH beside me was focusing on the overall quality of the animal, particularly the spiral horns, but beside him through the glasses I couldn't help noticing the striking markings as well.

Vertical pale stripes on the sides and flank of the kudu served to perfectly hide the animal in the shadowed light of the plains, and the stripes running from below the eyes to the bridge of the nose gave the animal a majestic and striking visage. I fine mane sprouted from the ridge of both the bottom and top line of the neck, and the tail ended in a superb fly-swatter of another bundle of darker hair.

Then, of course there were the horns; thickly-coiled and tall, divergent and widely spaced at the tips. I am no judge of trophy size, for as with most unfamiliar with the animals, they all looked big, but this was a beautiful specimen.

There is something special about the long-horned grey bulls, and even for those who have hunted them over and over, there is something about sighting one that causes your breath to catch in your chest.

"I think that you must shoot this Kudu" the PH whispered after further examination through the glasses, saying the words I wanted to hear. "He is good."

I only nodded in acknowledgement, for I was already getting set on the rifle. Over the sticks, I heard the safety catch click forward, and then the world shrunk, contracted, was drained of sound; narrowed down and was distilled into only a silent sight-picture and a long, slow squeeze of the trigger.

The big .375 crashed, and we were too close to hear the kugelschlag if there was one. The great, grey bandit was running, and I was busy working the bolt and trying to push the crosshairs ahead of the shoulder this time. When the rifle crashed again, it did so seemingly of its own volition. The lead was good, but the bullet passed over the back of the animal, but in just a few more long strides it stumbled and passed behind a low group of acacia bushes and fell to the ground, raising a big cloud of dust in the dry air.

"Better to take a second shot and not need it, than to need one and not take it", I thought to myself, as my pulse pounded in my neck and my hands began to shake.

"It is down...it is down" said the PH, watching the dust drift downwind. He did not whisper this time, but still spoke quietly.

Alone now with the kudu, my rifle and thoughts, I waited for the PH to return with the truck. There would be pictures, handshakes, and congratulations, for it was a fine animal. Crouched beside the still bull, I traced one finger along the perfect curl of the long ivory-tipped horns of a mature bull, while resting the opposite hand on its neck, feeling the warmth still there under the bristly short coat. It is an odd feeling, to be so still after so much noise and adrenaline, but it seems to be a fitting finale to the whole event, this quiet space after the hunt.

The day was warm, but not hot, but still the breeze was welcome. I turned into it, and pushed back the brim of my hat and let the wind caress my face, and cool the tears on my sunburned cheeks.

Even at the end of a long day of hunting, there is always enough energy left for one more stalk, should the quarry be of a sufficient measure. The PH and I were returning to camp after a successful impala hunt, and with the trophy care, butchering and incidentals taken care of, the walk in the red sand was a pleasant and relaxed affair, with none of the stealth and care that a stalk demands. We talked of past hunts; triumphs, defeats, oddities and excitements, and as this is Africa, and in Africa one finds animals that do not necessarily run at the scent of man, the conversation eventually drifted to the topic of lions.

The hunting camp we were returning to is situated only a few hundred meters from the wildness of the Kgalandi Transfrontier Park, which is a natural and ancestral habitat for the big cats. Days ago, with dark pressing in on the flickering light of the campfire, the PH had told stories of how the big cats would continually cross the border, looking for greener pastures and perhaps a bit of mutton to go with their usual diet of nearly everything else that roams wild in the veldt.

He told of the times that the roars had been so close in the night that they were wary in the early morning to venture out the door, and of finding large tracks in the sand all around the camp only meters from the thatched-roof buildings. Between the PH, his father and father-in-law, the numbers added up; certainly 30, probably 50 and maybe even over 60…each of those numbers representing another nightly marauder, a killer of livestock and threat to family. Blood on the sand is the only way.

So, with this in mind, walking back to camp, and spying my wife reading with her back turned to us on a high perch that overlooks the Botswana border, we decided that we could muster one more stalk today. Crouching and stepping carefully to be quiet, we silently tried to reach a spot of cover within earshot of the perch. Beginning our stalk, the had PH assured me that he could, on demand, roar like a particularly fierce lion, and so we worked our way closer, behind bushes only some 50 meters from where she sat. With a wide smile plastered comically on my tired face, I whispered to my guide that I hoped she had not loaded the rifle I left in the cabin. The smiles widened. Just a bit closer...

Suddenly, with the mental equivalence of air being released out of a balloon, our faces simultaneously fell, and we were met squarely with defeat, stripped of all pretense and wit, hearing the singsong words of challenge and condemnation from my wife that rained down on our heads, through the Kameeldoringboom to the bushes behind which we hid:

“I…"

“CAN…”

“SEE…”

“YOU…!!”

It is the first night in hunting camp, and as we walked to the Botswana border for something to do in the small amount of light still left to us, I found an old empty cartridge case uncovered by our plodding steps. The others continued on, not noticing me stop and stoop to pick it up. It was obviously old, smooth and almost weathered to a flat black.

As always, when I find an old tarnished case, I wonder of the hunter’s circumstances and the details of their day: Was this a shot fired in the heat of the chase, or only a practice shot to hone the eye and trigger finger? Did the bullet fly true, or was the action of the rifle worked with a disdainful shake of the head and a silent promise to do better with the next shot?

I wondered, too, if the shot was taken by one of the representatives of the three generations of proud Boers with which I walked, or if it came from a visitor or friend, not born and bred of the red sand. There was really no way of knowing, and so I made up my own tale with my own preferences, and slipped the case into my pocket for good luck for my own hunts to come.

Later, when I meant to take out the brass again from my pocket and found it missing, I couldn’t keep my irrational mind from wondering if I had never really held the old cartridge case in my fingers after all, but instead had found only a fragment of some old memory, or perhaps a leftover ghost from someone else’s past hunting tale.

The rooster had crowed, and pulling myself from bed I made my way to the sink to rinse the sleep from my tired eyes. Looking beside me through the partially open window, the full moon still stood in the slowly strengthening light; reigning over the Kalahari sands like a big heart in the morning sky, bringing to mind one of the few poems I can recite from memory complete:

In the sky,

Breath of juniper,

Wafting by.

If I should die,

While in your grace,

Eject my soul,

Into the place,

From which it came,

An empty book,

I’ll praise the time,

My journey took.

Comments for Bookends, Part Two

|

||

|

||

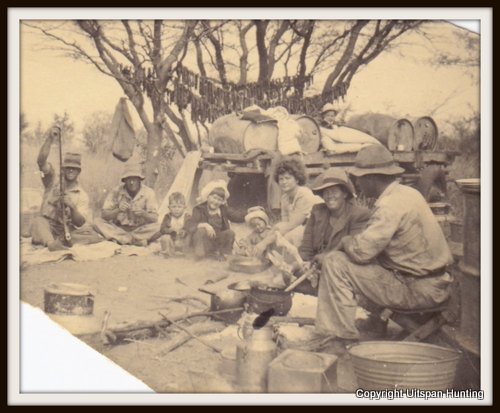

Meaning of "Uitspan"

'Uitspan' is an Afrikaans word that means place of rest.

When the Boer settlers moved inland in Southern Africa in the 1800's, they used ox carts. When they found a spot with game, water and green grass, they arranged their ox carts into a circular laager for protection against wild animals and stopped for a rest.

They referred to such an action of relaxation for man and beast, as Uitspan.

(Picture above of our ancestors.)

Did you know? Greater Southern Kudus are famous for their ability to jump high fences. A 2 m (6.56 ft) fence is easily jumped while a 3 m (9.84 ft) high fence is jumped spontaneously. These strong jumpers are known to jump up to 3.5 m (11.48 ft) under stress. |

Did you know? Some animals have one sense more than man!The flehmen response is a particular type of curling of the upper lip in ungulates, felids and many other mammals. This action facilitates the transfer of pheromones and other scents into the vomeronasal organ, also called the Jacobson's Organ. Some animals have one sense more than man!The flehmen response is a particular type of curling of the upper lip in ungulates, felids and many other mammals. This action facilitates the transfer of pheromones and other scents into the vomeronasal organ, also called the Jacobson's Organ.This behavior allows animals to detect scents (for example from urine) of other members of their species or clues to the presence of prey. Flehming allows the animals to determine several factors, including the presence or absence of estrus, the physiological state of the animal, and how long ago the animal passed by. This particular response is recognizable in males when smelling the urine of a females in heat. |